Land & Water Grabbing: Paying the price for Citrus

A journalist visited the Morocco-Sous Massa region and found several barren, abandoned farms and remnants of what used to be orange orchids around the town of Sebt El Guerdane. Springs, wells, and irrigation channels have dried up and farmers have left their farm in search for other jobs or migrated to cities. Below are some of the images captured. Yet, in the same region, some large citrus farms with access to canals of fresh water or government water pipelines and other farms who have dug deeper for groundwater have continued to thrive (James, 2016).

Images of Barren land, stumps of dead orange trees and piles of it ready to be turned in charcoal (Source: Desert Sun)

Images of Barren land, stumps of dead orange trees and piles of it ready to be turned in charcoal (Source: Desert Sun)

This is verified by Choukr-Allah et al. (2016) who states that about 4000 hectares of citrus orchards were lost due to water shortage in the Guerdane area and before the year 2008, at least 11,900 hectares of cultivated land was abandoned. In reality, while the Souss-Massa River Basin accounts for 85% and 55% of Morocco’s vegetable and citrus exports respectively, it is also inducing a water deficit (Choukr-Allah et al., 2016). The demands of water supply are fed by excessive groundwater extraction which exacerbates the lowering of water levels compounded by low aquifer recharge. This made farming increasingly difficult for small farmers who also could not afford better irrigation and dig deeper for groundwater (ibid). So, what could have contributed to this tragedy?

Perhaps the most obvious reasons would be to point at the large-scale agriculture and inefficient irrigation techniques. However, this conceals historical complexities such as power asymmetries, political and socio-economic factors. In fact, studies have revealed that land and water grabbing have indirectly contributed to the tragedy and can explain why there is a stark contrast of abandoned farms alongside thriving large-scale citrus agriculture.

The International Land Coalition defines large-scale land grabbing as acquisitions and concessions that violate human rights; disregarding human rights, social and economic impacts (Rulli et al., 2012). Behind every land grab is also a water grab which is broadly defined as where powerful actors are able to appropriate water resources at the expense of local communities or even the environment (Mehta et al., 2012).

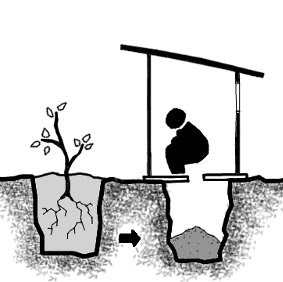

The Souss Valley have experienced an increasing control by elite and powerful actors over land and water resources for export-oriented agricultural such as lucrative citrus fruits (Houdret, 2012) eventually leading to overuse of water and groundwater depletion. This led to a public-private partnership (PPP) project (Fig 1.)which involved reallocating water through a 90km pipeline from the mountains to supply irrigation water for citrus agriculture. However, the PPP has contributed to land and water grabbing, exacerbating disparities between farmers(ibid) as the project infrastructures were mainly geared towards improving citrus produce. Although it was promoted promisingly and funded by locals, public and high authorities, Houdret (2012) criticizes that it is merely a form of political control over resources and profits.

Fig 1. Map of project, pipeline and dams (Source: Houdret, 2012)

The PPP has led to local communities being marginalized through processes embedded in its implementation(ibid). Firstly, the project restricts small-scale farmers from accessing ground and surface water and also drastically increased land value, restricting access to land as well. Secondly, the building of the two dams has displaced locals from confiscated lands with little or no compensation. Thirdly, it legalized existing and new groundwater drilling, allowing those who could afford to tap into the resource. Fourthly, the El Guerdane project showcases water grabbing through reallocation from small farmers and domestic users to citrus agriculture. This process of water and land governance forms a plural-legal mechanism in which powerful actors can exclude poor, marginalize people and entail ecological destruction reflecting of global politics of water grabbing (Franco et al., 2013). More specifically, the process identifies itself with blue water grabs (Angelo et al., 2018) which is defined as the appropriation of irrigation water in a region with existing irrigation constraints. All these favored the expansion of large farms who continued to exert their influence by buying more land from local farms, controlling land use by contracting farmers in PPP to practice citrus agriculture or indirectly impacting local farmers to abandon their farms due to groundwater depletion. Although large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) are not synonymous with land grabbing, debates on its impacts are polarised as capitalist restructuring of agriculture can catalyse positive impacts such as improve access to resource inputs and output productivity while on the other hand, opponents argue that LSLAs has negative impacts such as that of inequality in Guerdane and resource exploitation of the global south (Dell’Angelo et al., 2017).

As a result, land and water resources are not allocated equitably but with increasing inequality and increasing stress on water supply. The situation in Souss-Massa River Basin exemplifies that profit driven agriculture is squeezing the environment dry and teaches us that industrial agriculture promoted by land and water grabbers are simply not sustainable. Eventually, local communities have to the pay the price for the impacts. At the same time, it warns that private-public partnership should be carefully evaluated for its cascading impacts before similar false promises are implemented elsewhere.

Comments

Post a Comment