Ecosan: Improving Sanitation & Agriculture

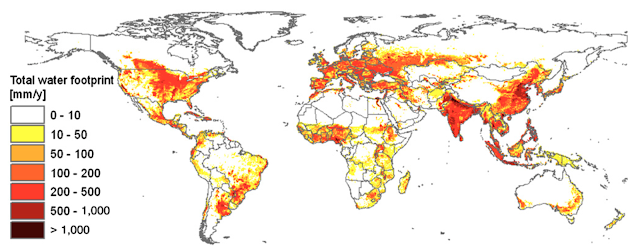

In sub-Saharan Africa, one of the challenges holding back agriculture activities from achieving a green revolution is soil degradation due to agriculture intensification (Tully et al, 2015) and a relatively low application of fertilisers that can increase crop productivity. Compared to the global average of more than 130kg of fertiliser per hectare of arable land, sub-Saharan uses less than 20kg (GRO, 2016). This is largely because chemical fertiliser remains financially and logistically costly as they are largely imported (ibid).

At the same time, with over 70% of the population without access to basic sanitation services and more than 20% still practicing open defecation (WHO, 2017), sanitation still remains far from the Sustainable Development Goals for sub-Saharan Africa. Interestingly, this seemingly unrelated issue to agriculture seems to spark some innovative solutions which also seeks to address agriculture fertilizer demands through the use of the collection of human waste matter. But can solving one problem also be a potential solution for another? Can human waste be a potential fertiliser for large-scale agriculture?

The fundamental idea of providing sanitation facilities and collection of human waste as useful products has seen many social enterprises kicking off around sub-Saharan Africa with varying implementation strategies. These ranges from simple compost toilets (E.g. Arborloo) to holistic sanitation approaches such as ecological sanitation (Ecosan) and even technologically advanced development like biosolids from human waste treatment. With a huge variety of potential solutions, how do we implement one that optimizes benefits for communities?

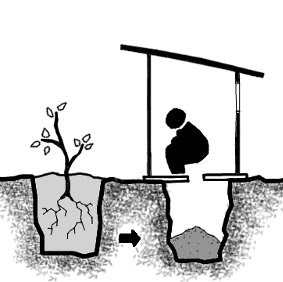

To begin, it is important to recognize the value and challenges in using human waste. Firstly, human urine contains high nitrogen proven to increase crop yields and is comparable with nitrogen fertilizer but at the same time contain low amounts of heavy metals that are detrimental to environment and groundwater (Sanders, 2014). In Uganda, the use of urine as a low-cost and low-risk practice have demonstrated that it can increase yield significantly in smallholder farms (Andersson, 2014). Secondly, human faeces although containing less nitrogen is capable of increasing organic content and water-holding capacity of soil (ibid). However, for use as fertiliser, it is recommended that urine and faeces are kept separated because microbes in faeces expel ammonia from urea in the urine (Drangert, 1998), worsening the stench. Design implementations such as urine-diverting toilets (UDTs) (Fig 1.) is an example of how urine and faeces are prevented from mixing at the source and collected in different containers. While there is a huge concern over pathogens in human urine and faeces, studies have shown that naturally high alkaline pH of urine kills pathogens and it can also be killed efficiently in faeces when properly composed (Sanders, 2014).

Traditionally, human waste is seen as a taboo subject which has led to the development of “flush and discharge” toilets and sewerage systems to minimize contact with human waste. Human waste presents itself similar to garbage matter as a parallax object (Moore, 2012) because of its characteristics (dirty, health risk of diseases like cholera) and seen as “out of place” and “disrupting sociospatial norms”(ibid). As such, the negative notions of human waste remains deeply embedded in cultural norms which are difficult to overcome and challenges the development of excreta management systems (Jewitt, 2011) capable of repurposing human waste as fertilizers.

Nonetheless, the benefits of human waste as fertilizers are promising and we should examine their feasibility in the context of sub-Saharan Africa.

Ecological Sanitation (Ecosan)

Ecosan is a paradigm that encapsulates the circular economy where human waste is recycled as inputs to “close” the loop (Esrey, 2001). It is important to note that Ecosan is not synonymous with the implementation of composting toilets and UDTs although they may be included in Ecosan broad range of approaches and principles (Langergraber & Muellegger, 2005). In the beginning, ecosan principle features treating excreta as near as possible to where people defecate and where water is not used as a transport medium for waste (Esrey, 2001). The collected human waste will then be subsequently treated by various means such as composting and then subsequently used in agricultural fertiliser applications. Today, Ecosan serves as a holistic framework (Fig 2.) for closing the loop on material flows (Langergraber & Muellegger, 2005). While the idea is not new and may even be part of indigenous practices historically, it has grown to include simple techniques such as compost toilets to technocentric solutions such as huge treatment plants.

Fig 2. Circular flows in an Ecosan System (Source: Langergraber & Muellegger, 2005).

Simple Composting Toilet – Arborloo

Arboloo is a low-cost, simple composting toilet that does not separate urine and faeces like UDTs which are popular in Zimbabwe. A minimalistic setup consist of a shallow pit, a squatting pan and a temporary movable shelter (Winblad et al., 2014) (Fig 3.). After each use, a mixture of soil, ash and leaves are added for composting to occur until it is almost full and it will be topped off with soil. The toilet infrastructure can then be moved to a new pit and the old pit can be used to plant fruit trees like citrus that have optimal nitrogen requirements.

Fig 3. Arboloo (Source: Winblad et al., 2014)

This is advantageous when pit emptying is not possible, and suitable in places with warm climates and have enough space(ibid) but have major drawbacks when not practiced appropriately. For example, this may lead to groundwater contamination, a potential of overflowing during floods and risk of pathogens when not treated properly since the process is overly simplified (Otterpohl and Buzie, 2011). Arguably, despite the risk, this would favour small-scale subsistence farmers who do not need to worry about specific guidelines for use of human excreta (WHO), unlike export-oriented farmers who would have to account for trade regulations and safety standards.

Sanergy

Sanergy is a Kenya-based social enterprise that builds ‘pay-to-use’ toilets in Nairobi for example that uses UDTs and collects waste daily which are then treated or composed to form organic fertilizer free of pathogens and in compliance with WHO standards. In their business models, this fertiliser was sold to local farmers and promoted on social media (Shields and Ruehle, 2016). While the containment of human waste in these toilets can be a great risk to public health when mismanaged (Mawioo et al, 2016), Sanergy is experimenting with new solutions to treat waste in Nairobi. Hence, in addressing sanitation issues, a social enterprise like Sanergy has created an economic opportunity under the ecological sanitation framework. However, profit-driven enterprise like Sanergy has positive and negative impacts on poverty (London and Esper, 2014) due to franchising and high-cost incurred from collection and treatment processes.

Instead of relying on fertiliser imports, Sanergy provides a potential solution to increase yield through locally produced organic fertilisers that are suitable for use for large-scale export-oriented agriculture as it meets the strict standards of WHO. It demonstrates that human waste can be a potential fertiliser for large-scale agriculture although in the beginning, farmers may not be receptive. Sanergy overcomes this through the building of trust on social media platforms and trials (Shields and Ruehle, 2016).

Best Implementations?

In seeking for the best implementation for communities, it is crucial to understand the local needs. Ecological Sanitation in Uganda has many more testimonials to share (NETWAS-U, 2011) and various other toilet systems and their advantageous and disadvantageous can found here. These strategies vary in different space and context but are seen to be embedded in local livelihoods without being disruptive. Ecosan and sanitation solutions examined in this post presents the fact that modern “flush and discharge” toilets are not the only answer to resolving sanitation problems in sub-Saharan Africa. While more developed countries like South Africa may turn to decentralized wastewater treatment facilities(Veolia) that can create biosolids for agriculture, low-tech solutions still remain viable to address problems in both sanitation and agricultural productivity in less-developed rural areas if local communities can be properly trained. Integrative solutions to address sanitation and agriculture productivity again should not be generalized and implemented without consulting respective stakeholders. In doing so, ecosan can provide an optimistic framework in which communities can continue to adapt to suit their growing needs.

This is a really detailed well structured post that I enjoyed reading as the sanitation-agriculture link is an interesting one. Do you think that there is too much stigma around 'dirt' and human waste for it to be feasibly used as an alternative to other fertilizers on a large scale? I know many farmers in the UK who are more than willing to use things like horse manure but would think twice about using human waste! It's interesting don't you think? (Mary Douglas has some great work on dirt and society and the way we view dirt as organising society/imposing rules upon society!)

ReplyDelete