From Agriculture to Agribusiness: Is Contract Farming the way forward?

Contract farming refers to an economic exchange between buyers(firms) and farmers where contractual agreements are signed. It creates vertical integration where firms have greater control over stages of the agriculture commodity chain before, during and after the cultivation of crops (Prowse, 2012). Often, agreements include the provision of better resources, stringent quality controls and guarantee sale of harvestable crops to buyers or access to markets among other possible terms and conditions. However, contract farming is not purely economic but also have social implications (Porter and Philips-Howard, 1997) embedded in the process as it affects people, livelihoods and social sustainability. Despite the benefits of contract farming, it has also resulted in hardships that have been well documented(ibid). So should contract farming be promoted? And if so, what defines a successful contract farming?

In sub-Saharan Africa, smallholder agriculture is the dominant economic activity but its nature is largely heterogeneous or uneven (Gollin, 2014). While there are advantages for the persistence of smallholder agriculture, they are also disadvantaged in areas such as market access. Today, contract farming is promoted as an inclusive business model for smallholder farms (SNRD) to gain market access and perceived as the way forward (AGRA, 2017). With the geography of commodity chains contingent on temporality, historical factors and contract farming has played a crucial role in ensuring social sustainability for smallholder farms. This is particularly exemplified in South Africa and its citrus agriculture.

Briefly, in the history of South Africa, an apartheid era has resulted in white farmers owning a majority of large-scale commercial farms whereas black farmers although greater in population size are engaged in smallholder farming mainly for subsistence. As such, contract agriculture can be seen as a form of opportunity to serve as an integration mechanism to allow smallholder farms to access market (Runsten & Key, 1996). From the 1980s, a series of events that caused the liberalisation of agriculture and increasingly stringent standards (Fréguin-Gresh and Anseeuw, 2010, p. 81) in the citrus industry also put smallholder farms at a disadvantageous position. Thus, contract farming becomes appealing as it promises a series of benefits, overcome these challenges and provide market access to smallholder farms especially black farmers probably seeking to improve their lives. These benefits that help smallholder transit into agribusiness includes (ibid):

1) Improving crop productivity with better resources (e.g. seeds, loans), capacity building and skill transfer

2) Overcoming transportation logistics from farm to packers and subsequent delivery to ports and international markets.

3) Transferring risk from farmers to contract buyers

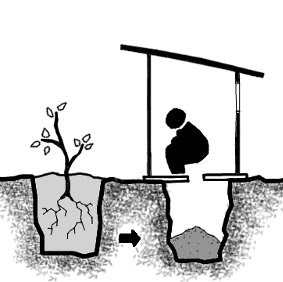

The following shows a summarised diagram on how an example of a citrus project in Letsitele (Limpopo province of South Africa) comprising of 62 smallholder farms interact under a contract with one citrus exporter:

(Source: Fréguin-Gresh and Anseeuw, 2010)

However, Fréguin-Gresh and Anseeuw (2010) also point out that contract farming is not fully inclusive and involves more privileged farmers in contrary to the belief that it could seek to reintegrate previously marginalized farmers. In addition, contract buyers are in greater control over the farm which means farmers have less authority and are also unable to withdraw without compensations if the need arises. Thus, forming contracts and partnerships is less empowering in the sense that farmers become reliant instead of becoming independent entrepreneurs (Bitzer and Bijman, 2014). In some cases, there have also been reports of conflicting interest between farmers and contract buyers due to the failure to recognize the importance of socio-economic importance and not investing enough in human and social capital (Musa et al., 2018). Unfortunately, such forms of contract are at best, just means of exploitation of smallholder farms as do not value add or help farmers out of poverty or improve their conditions. As such, perhaps a more flexible agreement where farmers have more autonomy in protecting their interest could be the way forward instead of being handheld by large firms through contracts.

In conclusion, contract farming is not all that glamorous. Where there are successful stories of contract farming, there are also failures. While it does have benefits that can catalyse economic transitions for smallholder farms, it is ultimately the contract characteristics and the external factors affecting the contract that truly controls a farm’s developmental trajectory. Contract farming should not be romanticised as the perfect solution to improving agriculture and stakeholders should carefully consider the frameworks involved to be fair and just to all parties involved. Nonetheless, efforts to improve smallholder farms is still a work in progress with many initiatives and contributions ongoing. In addition, more attention should be paid to how improvements in agribusiness processes can have greater positive influence on smallholder farms. As the saying goes, making small changes can go a long way.

x

Comments

Post a Comment