Commentary: Cape Town Water Crisis & Impacts on Citrus Agriculture

Briefly, under the direct influence of the recent severe drought (Wolski, 2018) resulting in low rainfall and dam levels, Cape Town is driven into a water crisis and a potential “Day Zero” situation where taps are turned off. This is compounded by a myriad of indirect influences such as mismanagement, power and political factors (Muller, 2018). While the crisis may seem to have been averted thanks to active local participation (Mahr, 2018), it is important to study the asymmetric impacts from the situation before taking appropriate actions. Specifically, this post will examine the agricultural industry in the region that have also suffered but have been overshadowed largely by media coverage on the city of Cape Town. Based on various online resources, this post will provide a commentary on the stakes involved in Cape Town Water Crisis and with a particular interest in export-oriented citrus production.

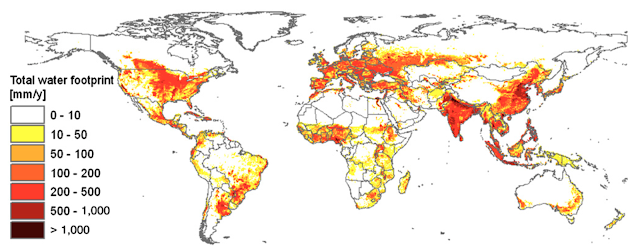

To understand the role of agriculture in the water crisis, it is important to identify that the Western Cape Water Supply System(WCWSS) which is a regional water management system provides 64% of its water supply to Cape Town and 29% to agriculture. While warnings in 2015 have called for 20% reduction in water usage, no restrictions have been placed on agriculture and water set aside for agriculture have even been reported to be over-allocated (Muller, 2017). Despite overlooked institutional management, farmers have been reported to reduce their water usage as much as 80% and farmers such as those in Groenland Water Users Association that are accustomed to the drying climate took the initiative to release water from their private dams back to Cape Town to help fight the water crisis. These water users associations are a group of water users in an area that ensures water is distributed equitably, assisting resource-poor farmers and also having a say in the municipal management of the resource. However, all these should not downplay or undermine the difficult reality for some growers in areas affected by the severe drought.

Amidst a water crisis, some farmers are forced to abandon farms and agricultural employment have dwindled (Mahr, 2018) and a host of other problems including farmers bankruptcy, suicides, high food prices and social unrest from job losses may surface (Johnston, 2018). In addition, across the Western Cape agriculture sector, there had been a 20.4% drop in production of crops including grapes and citrus from 2016 to 2018. With regards to export-oriented citrus agriculture, a prediction of 7.7% reduction in citrus production and income loses of R259 million is expected in 2018 for the region. Regardless of a reduction in citrus production in the Western Cape, there is still a clear inclination toward high-valued export crops in the form of citrus as seen in the 35% growth since 2014. On the overall export impacts, an increase in production of tangerines/mandarins in other regions of South Africa helped to minimize the decrease in export due to drought to about 2% whereas lemons/limes are estimated to increase by 7% (USDA, 2018). Therefore, South Africa is still expecting an overall record citrus crop this year as the fruit is coming to maturity recently. Clearly, the impacts on agriculture have been asymmetric or uneven as large-scale agricultural communities are able to curtail their use of water and impose measures with minimized losses whereas other less fortunate farmers including small-scale agriculture are susceptible to greater disruptions.

While highlighting the agricultural impacts and response alongside the cape town water crisis, I posit that the discussion of water management is inseparable in the wider discourse of socio-economic development, space and resource distribution. With competing dominant users in the Western Cape Supply System that is increasingly vulnerable to disruptions from drought events, is supporting an export-oriented agricultural in South Africa economy still sustainable?

Even though domestic users can impose water restrictions and regulations to curb with water shortages, the agricultural industry, on the other hand, is heavily dependent on water resources. Can agricultural growth be compromised to increase allowance on domestic use during times of water crisis? Or can agriculture look towards increasing their resilience to drought and reduce their water usage to allow more water for domestic users? The ability for farmers to release water to increase Cape Town’s local's resilience against Day Zero highlights a positive note on how dominant water users can have a considerable impact on each other in the Western Cape Supply System. As such, there is a need to evaluate the role of agriculture in the South African economy. Is planting citrus to satisfy global commodity demands a priority? Or is it time to re-evaluate agriculture water demands as Cape Town runs dry?

One thing for sure, either sides need to compromise and there will be trade-offs to achieve a fine balance and resilience against future drought events.

One thing for sure, either sides need to compromise and there will be trade-offs to achieve a fine balance and resilience against future drought events.

Thanks for this highly relevant post following up the water crisis in Cape Town over a year ago. Do engage as best you can with the peer-reviewed literature to develop your arguments as popular media is less likely to be robust than that which is peer-reviewed. Are there other locations in Africa where there is tension between agricultural and domestic uses of freshwater that you might cover?

ReplyDeleteHello! Thank you for reading and providing with feedbacks. Yes definitely! Conflicts between agricultural and domestic users of freshwater exist although they may be at very local scale which might not be easily picked up in the media or even peer-reviewed literature. However I did find an article on inter-user conflicts and intra-user conflicts which I find relevant to your question. The case study is set in the context of Namwala district in Zambia and seeks to examine the nature of the conflict to be considered for mitigation under water governance and Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) (Funder, 2010).

DeleteFunder, M., Mweemba, C., Nyambe, I., van Koppen, B., & Ravnborg, H. M. (2010). Understanding local water conflict and cooperation: The case of Namwala district, Zambia. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 35(13-14), 758-764.

I will be sure to look out for examples on water conflict and if it will be relevant in the subsequent blogpost. Thanks for the suggestion! =D

Lovely post, really enjoying your citrus theme. You point out that little reductions have been made to water use in the agricultural sector, often being over allocated. However say that poorer farmers are suffering. Is there any indication of how the decision for water allocation is made, is it based on the size and probability of your farm? Or would you say it is a largely racialised issue?

ReplyDeleteHello Joelle, Thanks for reading! While it remains unclear how water is allocated in the Western Cape Water Supply System, I hope to shed some light on how decision making in water allocation can be affected.

DeleteWater allocation on national scale is a highly intertwined, widely political and socio-economic topic that we can delve deep into and goes as far as understanding the dynamics and discourse of water allocation reform in South Africa which is still ongoing to redress inequalities. It can also be inherently implicated by intergovernmental institutes such as the OECD framework for water resources allocation. During the crafting of reforms, I postulate that there will be contesting economic (i.e. agriculture) and livelihood perspectives for the allocation of water. Thus, I would not say that water allocation is a radicalised issue so as to not undermine it.

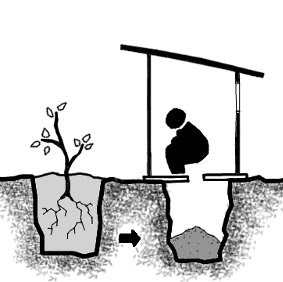

However, at a local scale, looking at Water User Associations (WUA), a bottom up approach to water governance, may shine some light on how water allocation is being made in the respective farms that has a shared irrigation system. WUA is an effort to decentralise irrigation management to provide equitable water resources for farms as well as provide other forms of support. It involves stakeholders to come together and discuss equitable water uses and include signing of contracts. Surely, one consideration would be size of the farm as well as many other individual factors that affect water demands (E.g. profits etc.) which will go into a feedback loop for accountability of resources. Whether or not WUA is effective remains debatable and varies in different context.

More about WUA can be read here: http://www.iwmi.cgiar.org/Publications/Working_Papers/working/wor180.pdf

Thank you!

Hey, thanks for this post! I read some of your blog posts and I am really enjoying them, they all provide insightful and detailed information, not to mention your citrus theme which is both original and funny :) this post is of particular interest to me as I also wrote one about Cape Town's water crisis, but with a political perspective. First, I would like to say that your focus on the citrus agriculture provides a different and perhaps more concrete idea of the crisis. For instance it made me realize the burden that farmers had to bear, and may bear even more with climate change in the next years/decades. Until I read your post I would rather have argued that too much water was allocated to agriculture, but now it makes me rethink it. Perhaps a good solution would be to engage in more sustainable agricultural practices so as to promote small holdings rather than large, intensive-farming industries. This would guarantee small farmers a living, while saving water for the other (notably municipal) needs. What would you say about it - do you have an idea how we could make sure water is allocated fairly and that this allocation remains sustainable environmentally?

ReplyDeleteIn any case, your post confronts me with a different perspective and it is very interesting!

Sarah Champagne